ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show

Most Recent Post

- Collecting Echinoids (Sea Urchins) in North Jutland, DenmarkToday, we have an interesting guest post from long-time ESCONI member Marie Angkuw. Marie is part of the Lyme Regis… Read more: Collecting Echinoids (Sea Urchins) in North Jutland, Denmark

- About ESCONI

- Around the Web

- Calendar of Events

- Code of Ethics and Conduct

- ESCONI Books for Sale

- ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show

- ESCONI in the News

- ESCONI Videos

- Field Trips

- Flashback Friday

- Fossil Friday

- Mazon Creek

- Mazon Monday

- Member Spotlight

- Membership Information

- Reference Material

- Throwback Thursday

- Trilobite Tuesday

Field trips require membership, but visitors are welcome at all meetings!

| Saturday, Jan 3rd | Mineralogy Study Group – 7:30 PM via Zoom “Critical Minerals: What are they and Opportunities in Illinois” presented by Dr. Jared Freiburg of the Illinois State Geological Survey. |

| Friday, Jan 9th | General Meeting – 8:00 PM via Zoom Jean-Pierre Cavigelli, Tate Geological Museum, Casper College, will present “Fossil Birds of Wyoming” |

| Saturday, Jan 10th | Junior Study Group – 6:30 PM, TBA Specifics of this meeting are available from Scott Galloway, 630-670-2591, gallowayscottf@gmail.com. The meeting will be in person at the College of DuPage Technical Education Center (TEC) Building – Room 1038A (Map). |

| Saturday, Jan 17th | Paleontology Study Group – 7:30 PM via Zoom “Getting Lost Can Lead to Treasure – Edrioasteroids – What to Do When You Find Thousands” by Jack Kallmeyer President, Dry Dredgers |

-

Collecting Echinoids (Sea Urchins) in North Jutland, Denmark

Read more: Collecting Echinoids (Sea Urchins) in North Jutland, DenmarkToday, we have an interesting guest post from long-time ESCONI member Marie Angkuw. Marie is part of the Lyme Regis Babes as John Catalani has named them. Marie, Rhonda Gates, Jann Bergsten, and Deborah Lovely have taken numerous trips to Europe to collect fossils. They’ve been to Lyme Regis (multiple times), Whitby, Yorkshire, and the […]

-

2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Preview #2: Fluorite, Galena, and Barite From Bingham, NM

Read more: 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Preview #2: Fluorite, Galena, and Barite From Bingham, NMThis is the preview post #2 for the 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show Live Auction. The ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show for 2026 will be held on March 21th and 22nd at the DuPage Fairgrounds in Wheaton, IL, which is the same location as last year. All details can be found here. In […]

-

Mazon Monday #306: Drevotella proteana

Read more: Mazon Monday #306: Drevotella proteanaThis is Mazon Monday post #306. What’s your favorite Mazon Creek fossil? Tell us at email:esconi.info@gmail.com. Drevotella proteana is believed to be a hydrozoan. It lived during the Pennsylvanian Period. Fossils of this soft-bodied animal are known only from the Mazon Creek fossil deposit, where exceptional preservation allows such delicate organisms to be recorded. Hydrozoans […]

-

Chicago Rocks & Minerals Society’s Annual Silent Auction, Saturday, March 14, 2026

Read more: Chicago Rocks & Minerals Society’s Annual Silent Auction, Saturday, March 14, 2026Chicago Rocks & Minerals Society’s Annual Silent Auction Saturday, March 14, 2026 6 to 9 p.m. St. Peter’s United Church of Christ 8013 Laramie Ave., Skokie, IL (Across the street from the public library on Oakton) Plus a special live auction of high-end specimens during the last half-hour! The first table closes at 6:30 p.m. […]

-

PBS: Inside the Vault Where They Keep the Dinosaur Apocalypse

Read more: PBS: Inside the Vault Where They Keep the Dinosaur ApocalypsePBS has an interesting video about the K-Pg extinction. Check it out! A giant asteroid impact ended the age of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. How did this mass extinction play out, moment by moment? In this video we meet a geologist who has explored the asteroid crater and learn what the rocks tell […]

-

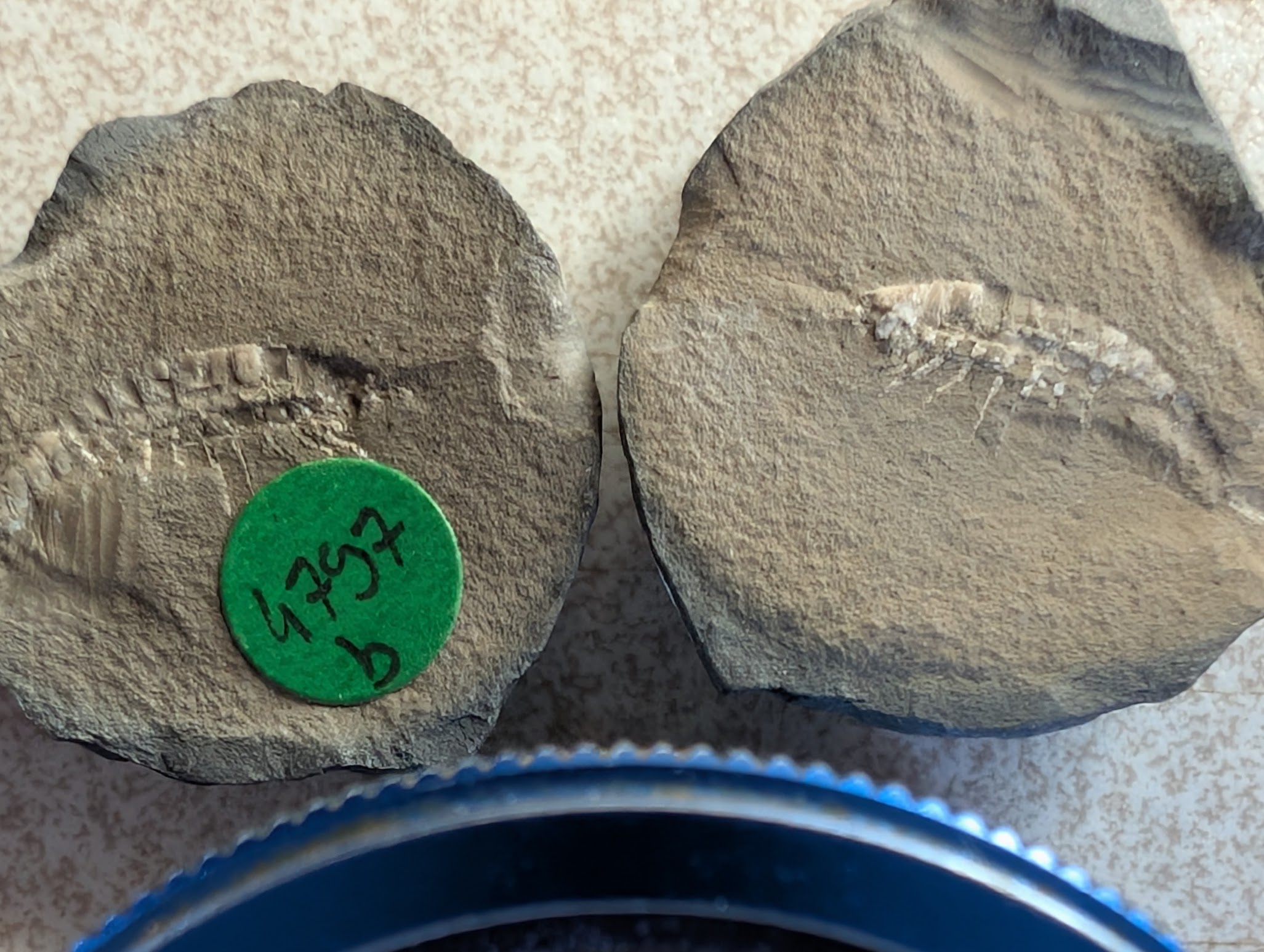

Fossil Friday #301: French Palaeocaris

Read more: Fossil Friday #301: French PalaeocarisThis is the “Fossil Friday” post #301. Expect this to be a regular feature of the website. We will post fossil pictures you send in to esconi.info@gmail.com. Please include a short description or story. Check the #FossilFriday Bluesky/Twitter hash tag for contributions from around the world! In Mazon Monday #294, we highlighted the fossil site at […]

-

Throwback Thursday #301: Century of Progress – Sinclair Exhibit

Read more: Throwback Thursday #301: Century of Progress – Sinclair ExhibitThis is Throwback Thursday #301. In these, we look back into the past at ESCONI specifically and Earth Science in general. If you have any contributions, (science, pictures, stories, etc …), please send them to esconi.info@gmail.com. Thanks! email:esconi.info@gmail.com. Ran across an interesting post on the Original Chicago Group on Facebook last month (December 2025). In […]

-

Video for ESCONI January 2026 Paleontology Meeting – “Getting Lost Can Lead to Treasure – Edrioasteroids”

Read more: Video for ESCONI January 2026 Paleontology Meeting – “Getting Lost Can Lead to Treasure – Edrioasteroids”Jack Kallmeyer President of the Dry Dredgers will present “Getting Lost Can Lead to Treasure – Edrioasteroids – What to Do When You Find Thousands”. The meeting was held on January 17th, 2026 at 7:30 PM. While growing my early collection in the Cincinnatian, one of the most desired fossils that I sought after was […]

-

Video for ESCONI January 2026 General Meeting – “Fossil Birds of Wyoming”

Read more: Video for ESCONI January 2026 General Meeting – “Fossil Birds of Wyoming”Jean-Pierre Cavigelli, of Casper College in Casper, WY, presented “Fossil Birds of Wyoming”. Wyoming’s fossil bird record spans much of the Late Cretaceous through the Cenozoic, though its completeness varies widely through time. The state’s oldest known bird fossils come from the late Cretaceous Mesa Verde Formation and Pierre Shale, dating to about 79 million […]

-

Mazon Monday #305: Herdina mirificus

Read more: Mazon Monday #305: Herdina mirificusThis is Mazon Monday post #305. What’s your favorite Mazon Creek fossil? Tell us at email:esconi.info@gmail.com. Herdina mirificus is an extinct species of short-winged insect, currently classified in the order Protorthoptera. Protorthoptera is an extinct lineage of insects that lived during the middle to late Pennsylvanian Period some 318 to 299 million years ago. The […]

-

PBS Eons: How Brawn Led to Brains

Read more: PBS Eons: How Brawn Led to BrainsPBS Eons has a new video. This one is about the evolution of brains. While we often think of brains as some kind of triumph over brawn, it turns out that those two things might not be mutually exclusive, and in fact, they’ve been linked for far longer than we might imagine. PBS Member Stations […]

-

There’s Something MUCH Bigger Than Yellowstone. And It Will Happen Again

Read more: There’s Something MUCH Bigger Than Yellowstone. And It Will Happen AgainPBS Terra has an interesting video about super volcanoes and they larger cousin… Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs). Yellowstone was massive. Roughly a thousand times larger than the eruption of Mt. St. Helens, the biggest eruption in the history of the continental United States. And if Yellowstone erupted again, the consequences for the U.S. and the […]

-

Fossil Friday #300: Orthotarbus robustus from the River

Read more: Fossil Friday #300: Orthotarbus robustus from the RiverThis is the “Fossil Friday” post #300. Expect this to be a regular feature of the website. We will post fossil pictures you send in to esconi.info@gmail.com. Please include a short description or story. Check the #FossilFriday Bluesky/Twitter hash tag for contributions from around the world! Is there a better way to post our 300th Fossil […]

-

Throwback Thursday #300: Poem… The Rockhound

Read more: Throwback Thursday #300: Poem… The RockhoundThis is Throwback Thursday #301. In these, we look back into the past at ESCONI specifically and Earth Science in general. If you have any contributions, (science, pictures, stories, etc …), please send them to esconi.info@gmail.com. Thanks! email:esconi.info@gmail.com. We have a poem this week. This poem appeared in the July 1970 edition of the ESCONI newsletter. […]

-

This Dinosaur Really Knew How to Get a Grip

Read more: This Dinosaur Really Knew How to Get a GripThe New York Times Trilobites column has an interesting story about a tiny egg stealing dinosaur that lived about 67 million years ago in what is now Mongolia. Manipulonyx reshetovi had a strange spike-covered hand, which provided its genus name meaning “manipulating claw”. The animal’s fossil was discovered in 1979 and described in the journal […]

-

ESCONI January 2026 Paleontology Meeting – January 17th, 2026 at 7:30 PM – “Getting Lost Can Lead to Treasure – Edrioasteroids”

Read more: ESCONI January 2026 Paleontology Meeting – January 17th, 2026 at 7:30 PM – “Getting Lost Can Lead to Treasure – Edrioasteroids”Jack Kallmeyer President of the Dry Dredgers will present “Getting Lost Can Lead to Treasure – Edrioasteroids – What to Do When You Find Thousands”. The meeting will be held on January 17th, 2026 at 7:30 PM. While growing my early collection in the Cincinnatian, one of the most desired fossils that I sought after […]

-

Mazon Monday #304: Field Museum… Illinois by the sea

Read more: Mazon Monday #304: Field Museum… Illinois by the seaThis is Mazon Monday post #304. What’s your favorite Mazon Creek fossil? Tell us at email:esconi.info@gmail.com. In May 1970, the Field Museum opened an exhibit about Mazon Creek. It was called “Illinois by the sea: a coal age environment” and ran from May 25th until September 25th. It was a successful exhibit that featured Field […]

-

NPR Short Wave: The dinosaur secrets found in the archives of a natural history museum

Read more: NPR Short Wave: The dinosaur secrets found in the archives of a natural history museumNPR’s Short Wave show has an episode about dinosaurs at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. What happens behind the scenes of a dinosaur exhibit? Short Wave host Regina Barber got to find out … by taking a trip to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. In the museum’s basement, she talked to […]

-

The Year in Neanderthals

Read more: The Year in NeanderthalsThe New York Times has a nice article that highlights new understanding into who the Neanderthals were. Neanderthals lived across Eurasia for hundreds of thousands of years before going extinct some 40,000 years ago. A bunch of new high profile studies were published in 2025. Barely three decades ago, these ancient hominids were still being […]

-

Fossil Friday #299: Annularia sphenophylloides

Read more: Fossil Friday #299: Annularia sphenophylloidesThis is the “Fossil Friday” post #299. Expect this to be a regular feature of the website. We will post fossil pictures you send in to esconi.info@gmail.com. Please include a short description or story. Check the #FossilFriday Bluesky/Twitter hash tag for contributions from around the world! Today, we have another beautiful contribution from George Witaczek. This time […]