ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show

Most Recent Post

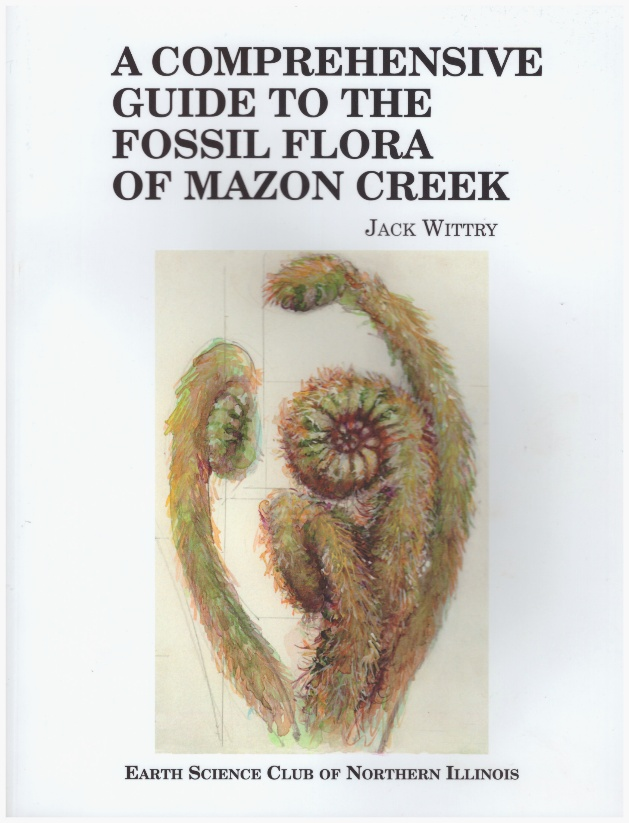

- ESCONI Books and Items for SaleESCONI actively sells our Club’s new books on Mazon Creek fossils that were written by Jack Wittry (an Honorary Club… Read more: ESCONI Books and Items for Sale

- About ESCONI

- Around the Web

- Calendar of Events

- Code of Ethics and Conduct

- ESCONI Books for Sale

- ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show

- ESCONI in the News

- ESCONI Videos

- Field Trips

- Flashback Friday

- Fossil Friday

- Mazon Creek

- Mazon Monday

- Member Spotlight

- Membership Information

- Reference Material

- Throwback Thursday

- Trilobite Tuesday

Field trips require membership, but visitors are welcome at all meetings!

| Friday, February 13th | General Meeting – 8:00 PM via Zoom Dale Simpson will present “Diggin’ Illinois: A hands-on introduction to the fascinating archaeological record of Illinois.” |

| Saturday, February 14th | Junior Study Group – 2:00 PM, Topic “Lighted Display Tracing Rock, Mineral and Fossil Specimens” by Finn Lutz, ESCONI Member Specifics of this meeting are available from Scott Galloway, 630-670-2591, gallowayscottf@gmail.com. The meeting will be in person at the College of DuPage Technical Education Center (TEC) Building – Room 1038A (Map). |

| Saturday, February 21st | Paleontology Study Group – 7:30 PM via Zoom Arvid Aase will present “Death to Discovery: Taphonomy of the Fossil Lake Lagerstatten (Green River Group).“ |

| No meeting this month | Mineralogy Study Group |

-

ESCONI Books and Items for Sale

Read more: ESCONI Books and Items for SaleESCONI actively sells our Club’s new books on Mazon Creek fossils that were written by Jack Wittry (an Honorary Club member). We also sell other ESCONI-branded items such as T-shirts, hats, mugs, ornaments, memory sticks, etc., in addition to used books that are donated to the Club. These items are for sale at ESCONI’s annual March Show and at various other Club events. Some of these items are sold by ESCONI on eBay. To find these books and items on eBay using your computer: Your computer’s browser may have some slight variances in the steps. If you are using your…

-

Reminder: Chicago Rocks & Minerals Society’s Annual Silent Auction, Saturday, March 14, 2026

Read more: Reminder: Chicago Rocks & Minerals Society’s Annual Silent Auction, Saturday, March 14, 2026Chicago Rocks & Minerals Society’s Annual Silent Auction Saturday, March 14, 2026 6 to 9 p.m. St. Peter’s United Church of Christ 8013 Laramie Ave., Skokie, IL (Across the street from the public library on Oakton) Plus a special live auction of high-end specimens during the last half-hour! The first table closes at 6:30 p.m. Bid on minerals, fossils, crystals, geodes, gemstones, handmade jewelry, rough rock, books, magazines, and lapidary treasures galore. Families are welcome; children must be accompanied by an adult. Free admission. Free parking. For more information, contact Jeanine N. Mielecki, (312) 623-1554 or email jaynine9@aol.com or visit http://chicagorocks.org. Follow…

-

2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Vendor List

Read more: 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Vendor ListThe 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show will be here before you know it! Here is the vendor list. Exclusive Inspirations Wisconsin Janski Designs Illinois Rock’s Rocks Illinois Rock Stars Illinois Michael’s Mineral Exchange Illinois Fossil Hut Illinois Grab Your Rocks Illinois Lavin’s Gems Illinois KP Rocks and Minerals Michigan RockhoundMike Minerals Illinois Joe’s Jems Illinois Of The Earth Elements Illinois ReVibe Crystals Illinois Adventures in Stone Illinois Paleocasts Illinois Dragon’s Hoard Minerals Illinois Adam Holm Illinois Rocks, Minerals and Things Iowa Mighty Gem and Mineral Co. Illinois Mystic Moraine Minerals Wisconsin

-

Fossil Friday #306: Cyclus obesus

Read more: Fossil Friday #306: Cyclus obesusThis is the “Fossil Friday” post #306. Expect this to be a regular feature of the website. We will post fossil pictures you send in to esconi.info@gmail.com. Please include a short description or story. Check the #FossilFriday Bluesky/Twitter hash tag for contributions from around the world! Mazon Monday #310 was about Cyclus obesus. That post was triggered by Mike Monteith’s recent find. On one of the nice days last week, Mike was going through his freeze/thaw from this winter and found this very nice Cyclus obesus. Thanks for sharing, Mike!

-

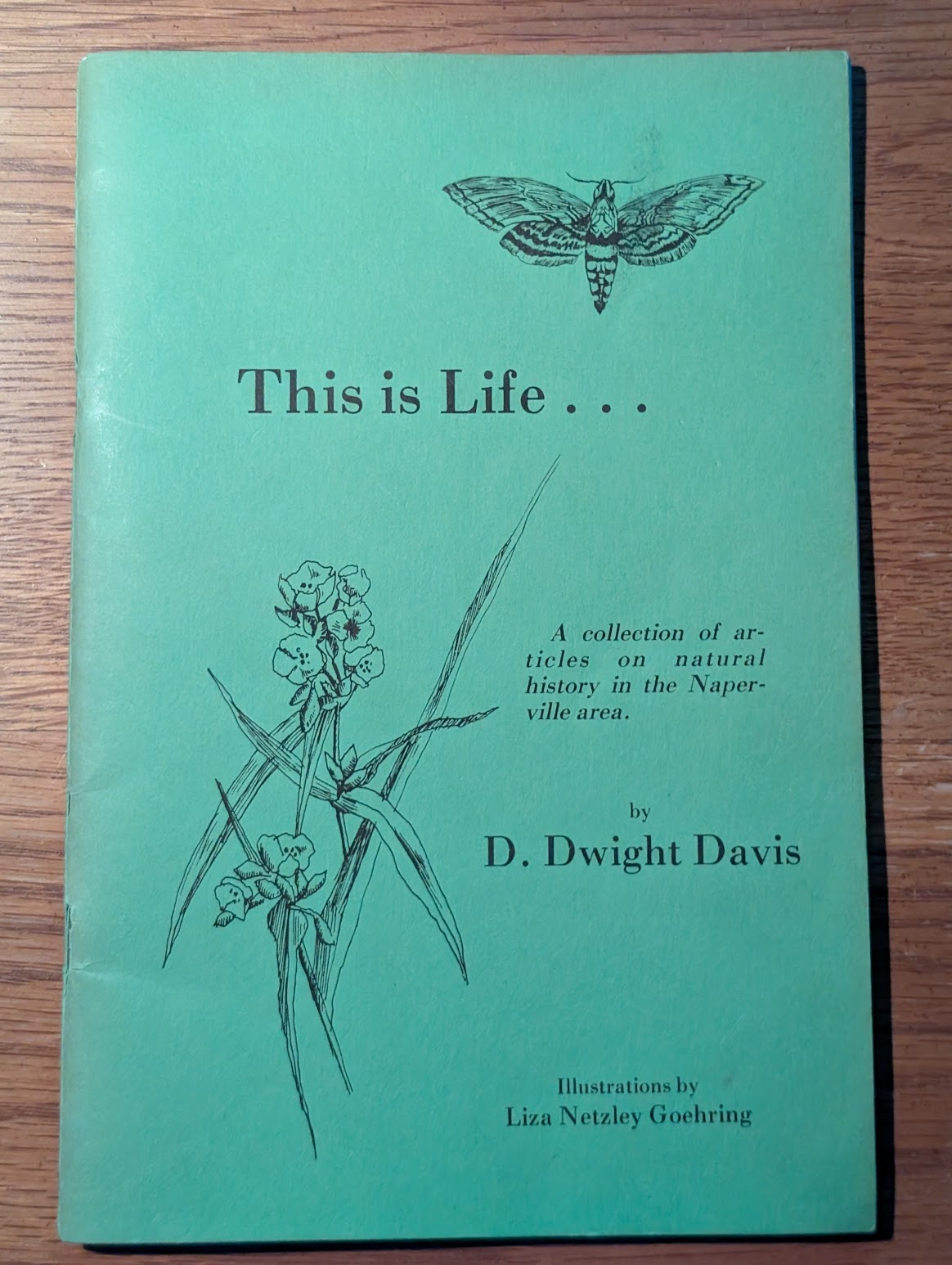

Throwback Thursday #306: This is Life…

Read more: Throwback Thursday #306: This is Life…This is Throwback Thursday #306. In these, we look back into the past at ESCONI specifically and Earth Science in general. If you have any contributions, (science, pictures, stories, etc …), please send them to esconi.info@gmail.com. Thanks! email:esconi.info@gmail.com. I received an interesting book from Bob Goss last November. You may remember him from a couple Fossil Friday’s (Fossil Friday #284 Alethopteris lonchitica/Alethopteris serlii and Fossil Friday #297 Alethopteris serlii), which both featured beautiful Mazon Creek seed-ferns collected by his father, Cecil Goss. Cecil Goss was a Methodist pastor with a passion for fossil and mineral collecting. He was pastor of the…

-

Ticks, Ticks, Ticks, Ticks, Ticks 2026!

Read more: Ticks, Ticks, Ticks, Ticks, Ticks 2026!You will probably be getting outside more soon looking for fossils, minerals, etc. in the woods, fields, and quarries. Or at least, that’s what we hope… after all, this is the ESCONI website. And, remember fossil collecting season opens up on March 1st at Mazonia South. However, thanks to our mild winter and that early February warm spell, the ticks are getting early this year. Ticks are more than just a nuisance; they are vectors for several serious diseases. In Illinois, keep an eye out for these common species: Stay Safe: Before you head out, make sure to “spray up”…

-

2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Preview #7: Paleoctopus newbolti from Lebanon

Read more: 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Preview #7: Paleoctopus newbolti from LebanonThis is the preview post #7 for the 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show Live Auction. The ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show for 2026 will be held on March 21th and 22nd at the DuPage Fairgrounds in Wheaton, IL, which is the same location as last year. All details can be found here. We have something a little different for today’s preview… a fossil squid from the Cretaceous. This animal, Paleoctopus newbolti, was found in the Late Cretaceous Period deposits of Lebanon. It’s not as famous as other lagerstatten, but the Lebanese lagerstatten has very finely preserved plants and…

-

Paleontologist Dr. Hans-Dieter Sues RIP (1956-2026)

Read more: Paleontologist Dr. Hans-Dieter Sues RIP (1956-2026)We are sad to hear of the sudden passing of Dr. Hans-Dieter Sues, Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Here is the Smithsonian’s announcement on Facebook. It is with profound sadness that we share the news that our friend and colleague Dr. Hans-Dieter Sues, Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology, unexpectedly passed away this weekend. After receiving his Ph.D. from Harvard, he was a postdoctoral fellow at McGill University and our museum. Following a distinguished career at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, he returned here as the…

-

Mazon Monday #310: Cyclus obesus

Read more: Mazon Monday #310: Cyclus obesusThis is Mazon Monday post #310. What’s your favorite Mazon Creek fossil? Tell us at email:esconi.info@gmail.com. Cyclus obesus is one of four species of Cycloidea found in Mazon Creek. It was described in the paper “Mazon Creek Cycloidea” by Frederick Schram. The paper was published in the Journal of Paleontology in 1997. In that paper, Schram established three new species of Cycloidea… Cyclus obesus, new species, Halicyne max, new species, and Apionicon apioides, new genus, new species. The new ones joined Cyclus americanus (see Mazon Monday #28), which was described by Alpheus Spring Packard (1839-1905) in 1885. Abstract of “Mazon Creek Cycloidea“ The Mazon Creek…

-

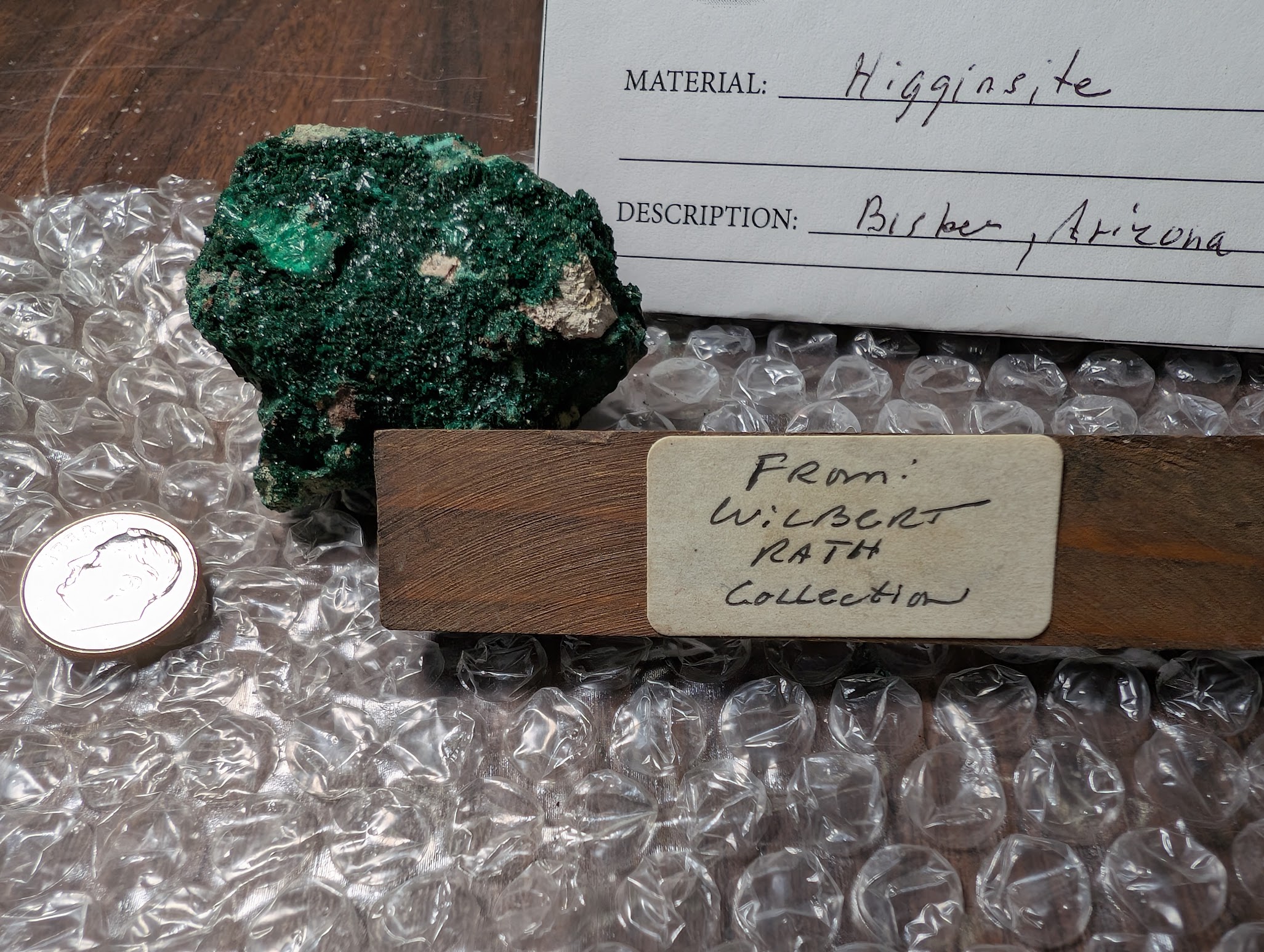

2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Preview #6: Higginsite from Bisbee, Arizona

Read more: 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Preview #6: Higginsite from Bisbee, ArizonaThis is the preview post #6 for the 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show Live Auction. The ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show for 2026 will be held on March 21th and 22nd at the DuPage Fairgrounds in Wheaton, IL, which is the same location as last year. All details can be found here. We are inside a month to the show… need to ramp up the previews, so check back often as we will be posting them more often. We have 100+ specimens for the live auction, stay tuned! Here is a nice Higginsite specimen from Bisbee, Arizona. This…

-

ESCONI at the Ranch View STEAM Event in Naperville

Read more: ESCONI at the Ranch View STEAM Event in NapervilleFor the second year, ESCONI was asked to participate in the Ranch View Elementary STEAM event in Naperville. Represnting the club were Jodi Gosain, Rusty Grenier, and Jim Bigler. The club had three tables of fossils, rocks, geodes, magnetic stones and our popular dig box. Over 300 parents and children attended our booth. In addition, Rusty Grenier had an opportunity to meet up with his creation in the school’s library. Last year, ESCONI donated to the school a model Styracosaurus that Rusty had made and donated to the club.

-

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

Read more: New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central SaharaPhys.org has a story about a new species of spinosaurus. Spinosaurus mirabilis was found in Niger at a remote locale in the central Sahara by a team of 20 researchers led by Paul Sereno, Ph.D., Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago. The animal is described in the paper “Scimitar-crested Spinosaurus species from the Sahara caps stepwise spinosaurid radiation” which was published in the journal Science. In November 2019, the team found a scimitar-shaped crest and some jaw fragments on the desert surface. It was only later on a return trip in 2022 when they found two more…

-

Fossil Friday #305: A Beautiful Receptaculites/Fisherites!

Read more: Fossil Friday #305: A Beautiful Receptaculites/Fisherites!This is the “Fossil Friday” post #305. Expect this to be a regular feature of the website. We will post fossil pictures you send in to esconi.info@gmail.com. Please include a short description or story. Check the #FossilFriday Bluesky/Twitter hash tag for contributions from around the world! Taking a little break from Mazon Creek fossils this week with a beautiful, complete Receptaculites, sp. (Fisherites) from Northern Illinois. In Illinois, Receptaculites are rarely found complete. This one appears to be very nicely preserved. It was sent in by Gregg Weiner, who found it in a creek near his house. Their phylogenetic origin has…

-

Throwback Thursday #305: The Sinclair Dinosaurs at the New York World’s Fair in 1964-1965

Read more: Throwback Thursday #305: The Sinclair Dinosaurs at the New York World’s Fair in 1964-1965This is Throwback Thursday #305. In these, we look back into the past at ESCONI specifically and Earth Science in general. If you have any contributions, (science, pictures, stories, etc …), please send them to esconi.info@gmail.com. Thanks! email:esconi.info@gmail.com. The Sinclair Oil company was formed by Harry Sinclair in 1916. The dinosaur known as “Dino” first appeared in marketing materials in 1930. It proved very popular with not only children but the general public. Sinclair’s dinosaur exhibit at the Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, in 1933, was very successful. So, Sinclair decided to use their…

-

ESCONI January 2026 Paleontology Meeting – February 21st, 2026 at 7:30 PM – “Death to Discovery: Taphonomy of the Fossil Lake Lagerstatten”

Read more: ESCONI January 2026 Paleontology Meeting – February 21st, 2026 at 7:30 PM – “Death to Discovery: Taphonomy of the Fossil Lake Lagerstatten”Arvid Aase , Head Curator at Fossil Butte National Monument in Wyoming, will present “Death to Discovery: Taphonomy of the Fossil Lake Lagerstatten (Green River Group).” Lakes are divided into three types: overfilled, balance-filled, and under-filled. The characteristics of a balance filled lake create the greatest opportunity for conditions conducive to fossil preservation. Fossil Lake was all three lake types through its 2-million-year existence during the Early Eocene. Not all sediment deposited during balance-filled episodes preserved abundant, well-preserved fossils, but all highly fossiliferous layers were deposited during balance-filled episodes. The ten most important conditions are explained. The mineralizing component of…

-

2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Preview #5: Large Archimedes sp. from Alabama

Read more: 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show – Preview #5: Large Archimedes sp. from AlabamaThis is the preview post #5 for the 2026 ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show Live Auction. The ESCONI Gem, Mineral, and Fossil Show for 2026 will be held on March 21th and 22nd at the DuPage Fairgrounds in Wheaton, IL, which is the same location as last year. All details can be found here. Today’s preview is a very large and detailed Archimedes sp. bryozoan from the Bangor Formation in Northwestern Alabama.

-

Mazon Monday #309: Herbivory is Older Than We Thought!

Read more: Mazon Monday #309: Herbivory is Older Than We Thought!This is Mazon Monday post #309. What’s your favorite Mazon Creek fossil? Tell us at email:esconi.info@gmail.com. The Mann Lab at the Field Museum has been very busy. Their new paper “Carboniferous recumbirostran elucidates the origins of terrestrial herbivory” published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution has significant implications for the Mazon Creek ecosystem. This paper shows how even “old” ecosystems like the Sydney Mines and Mazon Creek are constantly being reinterpreted through new discoveries. Abstract The evolution of herbivory is one of the most important ecological events in the evolution of terrestrial vertebrates and impacted the ecosystems they inhabited.…

-

PBS Eons: 130 Million Years Ago, the World Caught Fire

Read more: PBS Eons: 130 Million Years Ago, the World Caught FirePBS Eons has a new video. This one is about the evolution of flowering plants. It seems that for flowering plants to take over the world, first they may have had to help burn the old one away…and then put those fires out.

-

ESCONI Field Trip to “Escape the Excavation” – College of DuPage – March 14th, 2026

Read more: ESCONI Field Trip to “Escape the Excavation” – College of DuPage – March 14th, 2026ESCONI will participate in a hands-on archaeological adventure on March 14th, 2026. The event will be in-person at the College of DuPage from 1:00 PM to 3:00 PM. This interactive workshop offers a hands-on archaeological “escape room” that invites participants to engage with curated archaeological remains. Blending problem-solving with experiential learning, Escape the Excavation will challenge participants to interpret evidence, decode context clues, and use archaeological reasoning to unlock each stage. Participants handle artifacts, examine site maps, and analyze indicators to reconstruct past lifeways and solve interconnected puzzles. By merging tactile engagement with collaborative inquiry, this format introduces core methods…

-

Des Plaines Valley Geological Society’s 61st Annual Jewelry, Mineral, Gem & Fossil Show, March 28-29, 2026

Read more: Des Plaines Valley Geological Society’s 61st Annual Jewelry, Mineral, Gem & Fossil Show, March 28-29, 2026Des Plaines Valley Geological Society’s 61st Annual Jewelry, Mineral, Gem & Fossil Show, March 28-29, 2026. Des Plaines Park District Leisure Center, 2222 Birch St., Des Plaines, IL. Sat. 9-5, Sun. 10-4. Adults $3, seniors $2, students over 12 or with school ID $1, children under 12 free when accompanied by an adult. Dealers, demonstrators, silent auction, geode cutting, kids’ activities, and door prize drawings. Contact Connie Lavin at (815) 222-8197, email Nival48@hotmail.com or call Mike Hanley at (847) 525-2941.